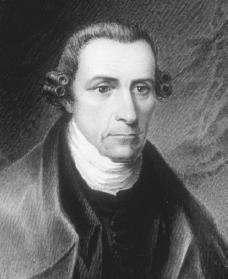

Patrick Henry Biography

Born: May 25, 1736

Studley, Virginia

Died: June 6, 1799

Red Hill, Virginia

American revolutionary, orator, and lawyer

Patrick Henry, American orator (public speaker) and lawyer, was a leader in Virginia politics for thirty years. He became famous for the forceful and intelligent way he spoke that persuaded people to believe in, and act upon, his beliefs. He used this gift to help bring about the American Revolution (1775–83).

A slow start

Patrick Henry was born in Hanover County, Virginia. He was the second son of John Henry, a successful Scottish-born planter, and Sarah Wynston Syme. He received most of his education from his father and his uncle. After his failed attempt as a storekeeper, he married Sarah Shelton and began a career as a farmer on land provided by his father-in-law.

Henry's farm days were cut short by a fire that destroyed his home. He and his growing family were forced to live above a tavern owned by his father-in-law. He earned money by working in the tavern. By 1760 Henry had decided to become a lawyer. He educated himself for about a year and then was admitted to the bar, an association for lawyers.

Eloquent patriot

By 1763 Henry had realized two things: he wanted to help the common people, and he had a gift for public speaking. While defending the members of a church from a lawsuit filed against them by church officials, Henry criticized the church for pushing its members around. He also criticized the British government, claiming that it encouraged the church in its disrespectful behavior. These arguments made Henry very popular,

Courtesy of the

Two years later, as a member of the House of Burgesses (the elective lawmaking body in the British colony of Virginia), he made a powerful speech against the Stamp Act. This law, passed by Britain in 1765, placed a tax on printed materials and business transactions in the American colonies. Henry also supported statements against the Stamp Act that were published throughout the Colonies and made him even more popular. For ten years Henry used his voice and wide support to lead the anti-British movement in the Virginia legislature.

The Revolution

During the crisis caused by the Boston Tea Party (a 1773 protest against Britain in which Boston colonists disguised as Native Americans dumped three shiploads of British tea into the harbor), Henry was at the peak of his career. He traveled with George Washington (1732–1799) and others to Philadelphia as representatives from Virginia to the First Continental Congress. The First Continental Congress was a group of colonial representatives that met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1774 to discuss their dissatisfaction with British rule. Henry urged the colonists to write in firm resistance toward Britain. "The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more," Henry said. "I am not a Virginian, but an American."

Elected to the first Virginia Revolutionary Convention in March 1775, Henry made one of the most famous speeches in American history. Trying to gain support for measures to arm the colony, Henry declared that Britain, by passing dozens of overly strict measures, had proved that it was hostile toward the colonies. "We must fight!" Henry proclaimed. "Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!" The representatives were greatly affected by Henry's powerful speech and Virginia rushed down the road to independence.

In 1775 Henry led a group of soldiers that forced the British to pay for gunpowder taken by British marines from an arsenal (a place where military weapons and equipment are made or stored) in Williamsburg, Virginia. He commanded the state's regular forces in Virginia for six months, but he eventually decided that he was not suited for a military role. At the Virginia Convention of May–July 1776, Henry supported the call for independence that led to the signing of the Declaration of Independence by Congress on July 4, 1776. In that same year, Henry was elected as the first governor of Virginia.

Devoted to Virginia

In three terms as wartime governor (1776–79), Henry worked effectively to use Virginia's resources to support Congress and George Washington's army. He also promoted the expedition of George Rogers Clark (1752–1818); the expedition drove the British from the Northwest Territory. During the years Henry served as governor, the legislature passed reforms that changed Virginia from a royal colony into a self-governing republic.

Henry left his post as governor in 1778 after serving two one-year terms to focus on family matters. His first wife had died in 1775, leaving him six children. Two years later he married Dorothea Dandridge, who was half his age and came from a well-known family of Tidewater, Virginia. Beginning in 1778, Henry had eleven children by his second wife, and family life kept him distracted from public life.

Still, Henry continued to serve in the Virginia assembly, engaging in verbal battles with other public speakers and focusing on efforts to expand Virginia's trade, boundaries, and power. Henry also served two more terms as governor of Virginia (1784–86). He grew more and more opposed to a stronger central government and refused to be a representative to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. He did not trust men like James Madison (1751–1836) from Virginia and Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804) from New York, fearing that they were too ambitious and too focused on the nation as a whole, overlooking the needs of individual states.

Peaceable citizen

At the Virginia Convention of 1788, Henry began a dramatic debate with Madison and his supporters. He called upon all his powers of speech to warn the representatives of the dangers that he felt would be created by the new Constitution. He feared that federal tax collectors would threaten men working peacefully on their own farms and that the president would prove to be a worse tyrant (a ruler who has absolute control) than even King George III (1738–1820) of Britain. Henry also insisted that the new federal government would favor British creditors (persons to whom money or goods are owed) and bargain away American rights to use the Mississippi River. Despite Henry's arguments, the Federalists (a political party that believed in a strong central government) managed to win a narrow victory. Henry accepted their victory by announcing that he would be "a peaceable citizen." He had enough power in the legislature, however, to make sure that Virginia sent anti-Federalist senators to the first Congress.

Once Henry's influence over Virginia politics began to weaken, he retired from public life. He returned to his profitable law practice, earning huge fees from winning case after case before juries that were impressed by his powerful pleas. He also increased his real estate holdings, which made him one of the largest landowners in Virginia. Although he was offered many appointments—as senator, as minister to Spain and to France, as chief justice of the Supreme Court, and as secretary of state—he refused them all. He was in poor health and preferred to stay home with his family. On June 6, 1799, Patrick Henry died of cancer at his plantation in Red Hill, Virginia.

For More Information

Mayer, Henry. A Son of Thunder: Patrick Henry and the American Republic. New York: F. Watts, 1986.

Meade, Robert D. Patrick Henry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1957–1969.

Sabin, Louis. Patrick Henry: Voice of the American Revolution. Mahwah, NJ: Troll Associates, 1982.

Tyler, Moses Coit. Patrick Henry. New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 1887. Reprint, New York: Chelsea House, 1980.

Vaughan, David J. Give Me Liberty: The Uncompromising Statesmanship of Patrick Henry. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Pub., 1997.