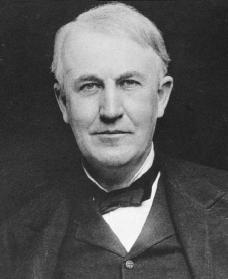

Thomas Edison Biography

Born: February 11, 1847

Milan, Ohio

Died: October 18, 1931

West Orange, New Jersey

American inventor

The American inventor Thomas Edison held hundreds of patents, mostly for electrical devices and electric light and power. Although the phonograph and the electric light bulb are best known, perhaps his greatest invention was organized research.

Early life

Thomas Alva Edison was born in Milan, Ohio, on February 11, 1847, the youngest of Samuel and Nancy Eliot Edison's seven children. His father worked at different jobs, including as a shopkeeper and shingle maker; his mother was a former teacher. Edison spent short periods of time in school but was mainly tutored by his mother. He also read books from his father's extensive library.

At the age of twelve Edison sold fruit, candy, and newspapers on the Grand Trunk Railroad between Port Huron and Detroit, Michigan. In 1862, using a small printing press in a baggage car, he wrote and printed the Grand Trunk Herald, which was circulated to four hundred railroad employees. That year he became a telegraph operator, taught by the father of a child whose life Edison had saved. Excused from military service because of deafness, he worked at different places before joining Western Union Telegraph Company in Boston in 1868. He also continued to read, becoming especially fond of the writings of British scientist Michael Faraday (1791–1867) on the subject of electricity.

First inventions

Edison's first invention was probably an automatic telegraph repeater (1864), which enabled telegraph signals to travel greater distances. His first patent was for an electric vote counter. In 1869, as a partner in a New York electrical firm, he perfected a machine for telegraphing stock market quotations and sold it. This money, in addition to that from his share of the partnership, provided funds for his own factory in Newark, New Jersey. Edison hired as many as eighty workers, including chemists and mathematicians, to help him with inventions; he wanted an "invention factory."

From 1870 to 1875 Edison invented many telegraphic improvements, including

Reproduced by permission of

Edison's most original and successful invention, the phonograph, was patented in 1877. From an instrument operated by hand that made impressions on metal foil and replayed sounds, it became a motor-driven machine playing soda can–shaped wax records by 1887. By 1890 he had more than eighty patents on it. The Victor Company developed from his patents. Edison's later dictating machine, the Ediphone, used disks.

Electric light

To research incandescent light (glowing with intense heat without burning), Edison and others organized the Edison Electric Light Company in 1878. (It later became the General Electric Company.) Edison made the first practical electric light bulb in 1879, and it was patented the following year. Edison and his staff examined six thousand organic fibers from around the world, searching for a material that would glow, but not burn, when electric current passed through it. He found that Japanese bamboo was best. Mass production soon made the lamps, while low-priced, profitable.

Prior to Edison's central power station, each user of electricity needed a generator, which was inconvenient and expensive. Edison opened the first commercial electric station in London in 1882. In September the Pearl Street Station in New York City marked the beginning of America's electrical age. Within four months the station was providing power to light more than five thousand lamps, and the demand for lamps exceeded supply. By 1890 it supplied current to twenty thousand lamps, mainly in office buildings, and to motors, fans, printing presses, and heating appliances. Many towns and cities installed central stations based on this model. Increased use of electricity led to numerous improvements in the system.

In 1883 Edison made a significant discovery in pure science, the Edison effect—electrons (particles of an atom with a negative electrical charge) flowed from incandescent conducting threads. With a metal plate inserted next to the thread, the lamp could serve as a valve, admitting only negative electricity. Although "etheric force" had been recognized in 1875 and the Edison effect was patented in 1883, the discovery was little known outside the Edison laboratory. (At this time existence of electrons was not generally accepted.) This "force" underlies radio broadcasting, long-distance telephone systems, sound pictures, television, X rays, high-frequency surgery, and electronic musical instruments. In 1885 Edison patented a method to transmit telegraphic "aerial" signals, which worked over short distances. He later sold this "wireless" patent to Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937).

Creating the modern research laboratory

In 1887 Edison moved his operations to West Orange, New Jersey. This factory, which Edison directed from 1887 to 1931, was the world's most complete research laboratory, with teams of workers investigating problems. Various inventions included a method to make plate glass, a magnetic ore separator, a cement process, an all-concrete house, an electric locomotive (patented in 1893), a nickel-iron battery, and motion pictures. Edison also developed the fluoroscope (an instrument used to study the inside of the living body by X rays), but he refused to patent it, which allowed doctors to use it freely. The Edison battery was perfected in 1910. After eight thousand trials Edison remarked, "Well, at least we know eight thousand things that don't work."

Edison's motion picture camera, the kinetograph, could photograph action on fifty-foot strips of film, sixteen images per foot. In 1893 a young assistant, in order to make the first Edison movies, built a small laboratory called the "Black Maria"—a shed, painted black inside and out, that revolved on a base to follow the sun and keep the actors visible. The kinetoscope projector of 1893 showed the films. The first commercial movie theater, a peepshow, opened in New York in 1884. A coin put into a slot activated the kinetoscope inside the box. In 1895 Edison acquired and improved Thomas Armat's projector, marketing it as the Vitascope. The Edison Company produced over seventeen hundred movies. Combining movies with the phonograph in 1904, Edison laid the basis for talking pictures. In 1908 his cinema-phone appeared, adjusting film speed to phonograph speed. In 1913 his kinetophone projected talking pictures: the phonograph, behind the screen, ran in time with the projector through a series of ropes and pulleys. Edison produced several "talkies."

Work for the government

During World War I (1914–18) Edison headed the U.S. Navy Consulting Board and contributed forty-five inventions, including substitutes for previously imported chemicals, defensive instruments against U-boats, a ship telephone system, an underwater searchlight, smoke screen machines, antitorpedo nets, navigating equipment, and methods of aiming and firing naval guns. After the war he established the Naval Research Laboratory, the only American organized weapons research institution until World War II (1939–45).

Synthetic rubber

With Henry Ford (1863–1947) and the Firestone Company, Edison organized the Edison Botanic Research Company in 1927 to discover or develop a domestic source of rubber. Some seventeen thousand different plant specimens were examined over four years—an indication of how thorough Edison's research was. He eventually was able to develop a strain yielding twelve percent latex, and in 1930 he received his last patent for this process.

The man himself

To help raise money, Edison called attention to himself by dressing carelessly, clowning for reporters, and making statements such as "Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration," and "Discovery is not invention." He scoffed at formal education, thought four hours of sleep a night was enough, and often worked forty or fifty hours straight, sleeping on a laboratory floor. As a world symbol of American inventiveness, he looked and acted the part. Edison had thousands of books at home and masses of printed materials at the laboratory. When launching a new project, he wished to avoid others' mistakes and tried to learn everything about a subject. Some twenty-five thousand notebooks contained his research records, ideas, hunches, and mistakes.

Edison died in West Orange on October 18, 1931. The laboratory buildings and equipment associated with his career are preserved in Greenfield Village, Detroit, Michigan, thanks to Henry Ford's interest and friendship.

For More Information

Baldwin, Neil. Edison: Inventing the Century. New York: Hyperion, 1995.

Cousins, Margaret. The Story of Thomas Alva Edison. New York: Random House, 1965.

Cramer, Carol, ed. Thomas Edison. San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2001.

Israel, Paul. Edison: A Life of Invention. New York: John Wiley, 1998.

Josephson, Matthew. Edison: A Biography. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: