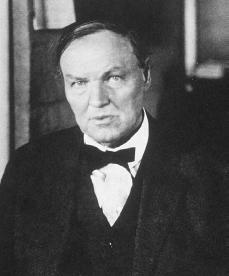

Clarence Darrow Biography

Born: April 18, 1857

Farmdale, Ohio

Died: March 13, 1938

Chicago, Illinois

American lawyer

As an American labor lawyer and as a criminal lawyer, Clarence Darrow participated in debates about the path of American industrial growth and the treatment of individuals in conflict with the law.

Early life

Clarence Seward Darrow was born on April 18, 1857, in Farmdale, Ohio, the fifth of Amirus and Emily Darrow's eight children. His father, after completing studies at a seminary (institution for training members of the priesthood), had lost his faith and become a nonbeliever living within a strongly religious community. (The Darrows were also outsiders in a political sense; they were Democrats in a strongly Republican area.) The elder Darrow worked as a carpenter and coffin maker. His mother, who died when he was fifteen, was a strong supporter of women's rights. From his parents Darrow received a love of reading and a skeptical (doubting) attitude toward religion.

Darrow, after completing his secondary schooling near Farmdale, spent a year at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, and another year at the University of Michigan Law School. Like most lawyers of the time, he delayed his admission to the bar until after he had studied under a local lawyer. He finally became a member of the Ohio bar in 1878. For the next nine years he was a typical small-town lawyer, practicing in the cities of Kinsman, Andover, and Ashtabula, Ohio. He married Jessie Ohl, the daughter

Courtesy of the

Seeking more interesting opportunities, however, Darrow and his family moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1887. In Ohio he had been impressed with the book Our Penal Machinery and Its Victims by Judge John Peter Altgeld. Darrow became a close friend of Altgeld, who was elected governor of Illinois in 1892. Altgeld not only raised questions about the process of criminal justice but, after pardoning several men who had been convicted for their part in the Haymarket riot of 1886 (a dispute between striking laborers and the Chicago police that led to the bombing deaths of seven policemen), he also questioned the treatment of those who were trying to organize workers into unions. Both of these themes played great roles in Darrow's life.

Labor lawyer

Darrow had begun as a common civil lawyer. Even in Chicago his first jobs included appointment as the city's corporation counsel in 1890 and then as general attorney to the Chicago and North Western Railway. In 1894, however, he began what would be his main career for the next twenty years—labor law. During 1894 he defended labor leader Eugene V. Debs (1855–1926) against a court order trying to break the workers' strike Debs was leading against the Pullman Sleeping Car Company. Darrow was unsuccessful, though; the order against Debs was finally upheld by the Supreme Court.

In 1906 and 1907 Darrow successfully defended William D. "Big Bill" Haywood, the leader of the newly formed Industrial Workers of the World, against a charge of plotting to murder the former governor of Idaho. But in 1911 disaster struck, as Darrow, while defending two brothers against a charge of killing twenty-one people by blowing up the Los Angeles Times building, was suddenly faced with his clients' changing their previous plea of innocent to guilty. There were also rumors that Darrow had attempted to bribe one of the members of the jury. As a result, Darrow was charged with misconduct, although he was found not guilty on all charges. This event ended his career as a labor lawyer, however.

Criminal lawyer

Darrow had always been interested in criminal law, in part because of his acceptance of new theories involving the role of determinism in human behavior. He believed that criminals were people led by outside factors (such as personality and environment) into committing unlawful acts. For this reason he was a bitter opponent of capital punishment, viewing it as an inhuman practice. Now he began a new major career as a criminal lawyer.

Without a doubt Darrow's most famous criminal trial was the 1924 Leopold-Loeb case, in which two Chicago college students had murdered a youngster simply to see if they could get away with it. For the only time in his career, Darrow insisted that his clients plead guilty. He then turned his attention to saving them from the death penalty. He was successful in this, partly because he was able to introduce a great deal of testimony from psychiatrists (doctors who deal with mental or behavioral disorders) supporting his theories regarding the determining influences on individual acts. In another successful case he defended members of an African American family charged with murdering a member of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK; a secret society whose members believe that white people are superior and who frequently resort to violence against nonwhite citizens) who had attempted to drive them from their home.

Scopes trial

During this period Darrow was also involved in another great American case, the Scopes trial of 1925 in Dayton, Tennessee. The issue was the right of a state legislature to prohibit the teaching in public schools of Charles Darwin's (1809–1882) theories of evolution (which suggested that the origins of humans and apes could be traced back to a common ancestor). Darrow, as a nonbeliever in religion and a believer in evolution, was annoyed with the religious tone of the law that had been passed. He sought to defend the young schoolteacher, John T. Scopes, who had raised the issue of evolution in his classroom. Technically, Darrow was unsuccessful, as Scopes was convicted and fined $100 for what the court believed was a crime. But Darrow's defense, and particularly his cross-examination of William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925), the three-time Democratic candidate for president who spoke for the religious, antiscientific side, won national attention and led many to question the wisdom of strict interpretation of the Bible.

Two books among Darrow's many writings are evidence of his interests toward the end of his life. In 1922 he wrote Crime: Its Cause and Treatment; in 1929 appeared Infidels and Heretics, coedited with Wallace Rice, in which he presented the case for free thinking. To these two issue-oriented books he added The Story of My Life (1932), an autobiography (the story of his own life). Darrow's last important public service was as chairman of a commission appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The commission examined the operation of the National Recovery Administration, an agency set up during the early 1930s to regulate industry competition and workers' wages and hours. Darrow died on March 13, 1938.

For More Information

Darrow, Clarence. Attorney for the Damned. Edited by Arthur Weinberg. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957. Reprint, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Darrow, Clarence. The Story of My Life. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1932. Reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Driemen, John E. Clarence Darrow. New York: Chelsea House, 1992.

Stone, Irving. Clarence Darrow for the Defense. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1941.