Daniel Webster Biography

Born: January 18, 1782

Salisbury, New Hampshire

Died: October 24, 1852

Marshfield, Massachusetts

American orator and lawyer

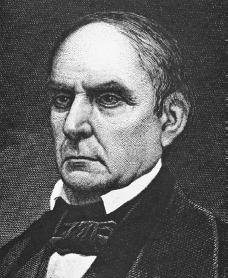

Daniel Webster, a notable public speaker and leading constitutional lawyer, was a major congressional spokesman for the Northern Whigs during his twenty years in the U.S. Senate.

Childhood

Daniel Webster was born in Salisbury, New Hampshire, on January 18, 1782. His parents were Ebenezer, who worked as a tavern owner and a farmer and was also involved in politics, and his second wife, Abigail. While a child, Daniel earned the nickname "Black Dan" for his dark skin and black hair and eyes. The second youngest of ten children, Daniel developed a passion for reading and learning at a young age. His formal education began in 1796 when he started at Phillips Academy in Exeter. Then when he was fifteen, Daniel went on to Dartmouth College.

After graduating from Dartmouth, Daniel studied law and was admitted to the bar (an organization for lawyers) in 1805. He opened a law office in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1807, where his success was immediate. He became a noted spokesman for the Federalists (a leading political party that believed in a strong federal government) through his addresses on patriotic occasions. In 1808 he married Grace Fletcher.

Early years in politics

Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1813, Webster reenergized the Federalist minority with his attacks on the war policy of the Republicans, the opposing political party. Under his leadership the Federalists often successfully obstructed war measures. After the War of 1812, when American and British forces clashed over shipping rites, he called for the restructuring of the Bank of the United States, but he voted against the final bill, which he considered defective. As the representative of a region where shipping was basic to the economy, he voted against the protective tariff (tax).

Webster left politics for a while when he moved to Boston, Massachusetts. As a result of his success in pleading before the U.S. Supreme Court, Webster's fame as a lawyer grew, and soon his annual income rose to fifteen thousand dollars a year. In 1819 Webster secured a triumph in defending the Bank of the United States in McCulloch v. Maryland. On this occasion Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall drew from Webster's brief the belief that the power to tax is the power to destroy. In 1824 Webster was also successful on behalf of his clients in Gibbons v. Ogden.

When Webster returned to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1823, his speeches began to attract national attention. From 1825 to 1829 Webster was one of the most faithful backers of President John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), supporting federal internal improvements and supporting Adams in his conflict with Georgia over the removal of the Cherokee Indians.

The Senator

When Webster was elected to the Senate in 1827, he made the first about-face in his career when he became a champion of the protective tariff. This shift reflected the growing importance of manufacturing in Massachusetts and his own close involvement with factory owners both as clients and as friends. It was largely due to his support that the "Tariff

Courtesy of the

In January 1830 Webster electrified the nation by his speeches in response to the elaborate explanations of the Southern states' rights doctrines (teachings) made by Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina. In memorable phrases Webster exposed the weaknesses in Hayne's views and argued that the Constitution (the document that states the principles of the American government) and the Union rested upon the people and not upon the states. These speeches, delivered before crowded Senate galleries, defined the constitutional issues which disturbed the nation for nearly thirty years.

The person

Webster was at the height of his powers in 1830. Regarded by others as one of the greatest orators (public speakers) of the day, he delivered his speeches with tremendous dramatic impact. Yet in spite of his emotional style and the passionate character of his speeches, he rarely sacrificed logic for effect. His striking appearance contributed to the forcefulness of his delivery. Tall, rather thin, and always clad in black, Webster's face was dominated by deep, luminous black eyes under craggy brows and a shock of black hair combed straight back.

In private Webster was more approachable. He was fond of gatherings and was a lively talker, although at times given to silent moods. His taste for luxury often led him to live beyond his means. While his admirers worshiped the "Godlike Daniel," his critics thought his constant need for money deprived him of his independence. During the Panic of 1837, a desperate financial crisis resulting from the expansion into western lands, he was in such desperate circumstances as a result of excessive investments in western lands that only loans from business friends saved him from ruin. Again, in 1844, when it seemed financial pressure might force him to leave the Senate, he permitted his friends to raise a fund to provide him with an income.

Secretary of State

Webster was one of the leaders of the anti-Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) forces that came together in the Whig party, a political party which opposed Jackson's Democrats. Regardless, Webster did endorse President Jackson's stand during the nullification crisis in 1832, where several states threatened to leave the Union unless granted the right to "nullify," or make void, certain federal laws. In 1836 the Massachusetts Whigs named Webster as their presidential candidate, but in a field against other Whig candidates he polled only the electoral votes of Massachusetts. In recognition of his standing in the party and in gratitude for his support during the campaign, President William Henry Harrison (1773–1841) appointed him secretary of state in 1841. He continued in this post under John Tyler (1790–1862), who succeeded to the presidency when Harrison died a month after he was sworn in as president. Among other accomplishments, Webster sent Caleb Cushing (1800–1879) to the Orient (Far East) to establish commercial relations with China, although he was no longer in office when Cushing concluded the agreement. Late in 1843 Webster, feeling that he no longer enjoyed Tyler's confidence, gave in to Whig pressure and retired from office.

Webster, in spite of his disappointment at not receiving the presidential nomination in 1844, actively campaigned for Henry Clay (1777–1852), his rival within the party. On his return to the Senate in 1844, Webster opposed the annexation (acception into the Union) of Texas and as well as the expansionist policies that peaked in the war with Mexico (1846–48), when American forces clashed with Mexico over western lands. After the war he worked to remove slavery from the newly acquired territories which resulted in the Wilmot Proviso.

Although Northern businessmen agreed, the average citizen was outraged over Webster's speech of March 1850 in defense of the new Fugitive Slave Law, a law that provided for the return of escaped slaves. Webster again became secretary of state in July 1850, in Millard Fillmore's Cabinet. In 1852 he lost his last hope for the presidency when the Whigs passed over him in favor of General Winfield Scott (1786–1866), a former Democrat. Deeply outraged, he refused to support the party candidate. He died just before the election on October 24, 1852.

For More Information

Baxter, Maurice G. One and Inseparable: Daniel Webster and the Union. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Lodge, Henry Cabot. Daniel Webster. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1883. Reprint, New York: Chelsea House, 1981.

Peterson, Merrill D. The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Remini, Robert V. Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

Also is there any family connection between Daniel Webster and the family of John C. Pillsbury (I

think the Pillsbury's lived in Vermont?