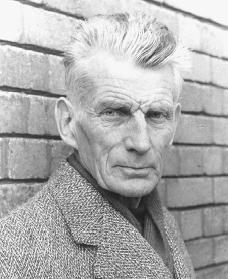

Samuel Beckett Biography

Born: April 13, 1906

Dublin, Ireland

Died: December 22, 1989

Paris, France

Irish novelist, playwright, and poet

Samuel Beckett, the Irish novelist, playwright, and poet was one of the most original and important writers of the twentieth century, winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969.

Early life in Ireland

Samuel Beckett was born in Dublin, Ireland, on April 13, 1906, to middle-class parents, William and Mary Beckett. Mary Beckett was a devoted wife and mother, who spent good times with her two sons in both training and hobbies. His father shared his love of nature, fishing, and golf with his children. Both parents were strict and devoted Protestants.

Beckett's tenth year came at the same time as the Easter Uprising in 1916 (the beginning of the Irish civil war for independence from British rule). Beckett's father took him to see Dublin in flames. Meanwhile, World War I (1914–18) had already involved his uncle, who was fighting with the British army. Here was the pairing of opposites at an early age: Beckett wrote of his childhood as a happy one, yet spoke of "unhappiness around me."

He was a quick study, taking on the French language at age six. He attended the Portora Royal boarding school in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, Ireland, where he continued to excel in academics and became the light-heavyweight boxing champion. He also contributed writings to the school paper. His early doodles were of beggar women, hoboes, and tramps. Schoolmasters often labeled him moody and withdrawn.

In 1923 he entered Trinity College in Dublin to specialize in French and Italian. His academic record was so distinguished that upon receiving his degree in 1927, he was awarded a two-year post as lecteur (assistant) in English at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, France.

Literary apprenticeship

In France Beckett soon joined the informal group surrounding the Irish writer James

Reproduced by permission of

Beckett returned to Dublin in 1930 to teach French at Trinity College. During the year he earned a Master of Arts degree. After several years of wandering through Europe writing short stories and poems and being employed at odd jobs, he finally settled in Paris in 1937.

First novels and short stories

More Pricks than Kicks (1934), a volume of short stories derived, in part, from the then unpublished novel Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1993), recounts episodes from the life of Belacqua. Belacqua, similar in character to all of Beckett's future heroes, lives what he calls "a Beethoven pause," the moments of nothingness between the music. But since what comes before and what follows man's earthly life (that is, eternity) are nothing, then life also (if there is to be continuity) must be a nothingness from which there can be no escape.

Beckett's first novel, Murphy (1938), is a comic tale complete with a philosophical (the search for meaning in one's life) problem that Beckett was trying to solve. As Murphy turns from the ugly world of outer reality to his own inner world, Beckett reflects upon the relationship between mind and body, the self and the outer world, and the meaning of freedom and love.

During World War II (1939–45; a war in which France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States fought against and defeated the combined powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan) Beckett served in the French Resistance movement (a secret organization of Jews and non-Jews who worked against the Nazis, the political party in control of Germany from 1933 until 1945). In 1953 he wrote another novel, Watt. Like each of his novels, it carries Beckett's search for meaning a step further than the preceding one, or, as several critics have said, nearer the center of his thought. In many respects Watt's world is everyone's world and he resembles everyone. Gradually Watt discovers that the words men invent may have no relation to the real meaning of the thing, nor can the logical use of language ever reveal what is illogical or unreasonable, the unknown and the self.

Writings in French

By 1957 the works that finally established his reputation as one of the most important literary forces on the international scene were published, and, surprisingly, all were written in French. Presumably Beckett had sought the discipline of this foreign language to help him resist the temptation of using a style that was too personally suggestive or too hard to grasp. In trying to express the inexpressible, the pure anguish (causing great pain) of existence, he felt he must abandon "literature" or "style" in the conventional sense and attempt to reproduce the voice of this anguish. These works were translated into an English that does not betray the effect of the original French.

The trilogy of novels Molloy (1951), Malone Dies (1951), and The Unnamable (1953) deals with the subject of death; Beckett, however, makes life the source of horror. To all the characters life represents a separation from the continuing reality of themselves. Since freedom can exist only outside time and since death occurs only in time, the characters try to rise above or "kill" time, which imprisons them. Recognizing the impossibility of the task, they are finally reduced to silence and waiting as the only way to endure the anguish of living. Another novel, How It Is, first published in French in 1961, emphasizes the loneliness of the individual and at the same time the need for others, for only through the proof of another can one be sure that one exists. The last of his French novels to be published was Mercier and Camier.

Plays and later works

Beckett reached a much wider public through his plays than through his novels. The most famous plays are Waiting for Godot (1953), Endgame (1957), Krapp's Last Tape (1958), and Happy Days (1961). The same themes found in the novels appear in these plays in a more condensed and accessible form. Later Beckett experimented successfully with other media: the radio play, film, pantomime, and the television play.

Beckett maintained a large quantity of output throughout his life, publishing the poetry collection, Mirlitonades (1978); the extended prose (writing that has no rhyme and is closest to the spoken word) piece, Worstward Ho (1983); and numerous novellas (stories with a complex and pointed plot) and short stories in his later years. Many of these pieces were concerned with the failure of language to express the inner being. His first novel, Dreams of Fair to Middling Women, was finally published after his death in 1993.

Although they lived in Paris, Beckett and his wife enjoyed frequent stays in their small country house nearby. Unlike his tormented characters, he was distinguished by a great serenity of spirit. He died peacefully in Paris on December 22, 1989.

Samuel Beckett differed from his literary peers even though he shared many of their preoccupations. Although Beckett was suspicious of conventional literature and theater, his aim was not to make fun of it as some authors did. Beckett's work opened new possibilities for both the novel and the theater that his successors have not been able to ignore.

For More Information

Cronin, Anthony. Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Dukes, Gerry. Samuel Beckett. New York: Penguin, 2001.

Knowlson, James. Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: