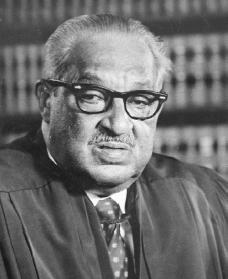

Thurgood Marshall Biography

Born: July 2, 1908

Baltimore, Maryland

Died: January 24, 1993

Bethesda, Maryland

African American Supreme Court justice and lawyer

Thurgood Marshall was an American civil rights lawyer, solicitor general, and the first African American to serve as associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. During his decades-long law career, Marshall worked for civil rights for all Americans.

Early life and schooling

Thurgood Marshall was born on July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, Maryland. He was the second child born to Norma Arica Williams, an elementary school teacher, and William Canfield Marshall, a waiter and country club steward. His family enjoyed a comfortable, middle-class existence. Marshall's parents placed great emphasis on education, encouraging Thurgood and his brother to think and learn. Whenever Thurgood got into trouble at school, he was made to memorize sections of the U.S. Constitution. This well-intended punishment would serve him well in his later legal career.

Courtesy of the

Marshall attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, working a number of jobs to pay his tuition. He became more serious about his studies after being suspended briefly in his second year. After receiving his bachelor's degree, he enrolled in the law school at Howard University in Washington, D.C., in 1930 and graduated in 1933. While at Howard he was influenced by Charles Houston (1895–1950) and other legal scholars who developed and perfected methods for winning civil rights lawsuits.

Civil rights lawyer

Passing the Maryland bar exam (an exam that is given by the body that governs law and that must be passed before one is allowed to practice law) in 1933, Marshall practiced in Baltimore until 1938. He also served as counsel for the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1935 he successfully attacked segregation (separation based on race) and discrimination (unequal treatment) in education when he participated in the desegregation of the University of Maryland Law School, to which he had been denied admission because of his race. Marshall became director of the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund in 1939. A year earlier he had been admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the fourth, fifth, and eighth circuits, and the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

After winning twenty-nine of the thirty-two civil rights cases that he brought before the Supreme Court, Marshall earned the reputation of "America's outstanding civil rights lawyer." During the trials, he and his aides were often threatened with death in the lower courts of some southern states. Some of the important cases he argued became landmarks in the ending of segregation as well as constitutional precedents (examples to help justify similar decisions in the future) with their decisions. These include Smith v. Allwright (1944), which gave African Americans the right to vote in Democratic primary elections; Morgan v. Virginia (1946), which outlawed the state's policy of segregation as it applied to bus transportation between different states; and Sweatt v. Painter (1950), requiring the admission of an African American student to the University of Texas Law School. The most famous was Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which outlawed segregation in public schools and more or less ended the practice once and for all. In addition, the NAACP sent Marshall to Japan and Korea in 1951 to investigate complaints that African American soldiers convicted by U.S. Army courts-martial had not received fair trials. His appeal arguments led to reduced sentences for twenty-two of the forty soldiers.

Presidential appointments

President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) nominated Marshall in September 1961 for judge of the Second Court of Appeals. Marshall was confirmed by the Senate a year later after undergoing extensive hearings. Three years later Marshall accepted an appointment from President Lyndon Johnson (1908–1973) as solicitor general. In this post Marshall successfully defended the United States in a number of important cases concerning industry. Through his office he now defended civil rights actions on behalf of the American people instead of (as in his NAACP days) as counsel strictly for African Americans. However, he personally did not argue cases in which he had previously been involved.

In 1967 President Johnson nominated Marshall as associate justice to the U.S. Supreme Court. Marshall's nomination was strongly opposed by several southern senators on the Judiciary Committee, but in the end he was confirmed by a vote of sixty-nine to eleven. He took his seat on October 2, 1967, becoming the first African American justice to sit on the Supreme Court. During his time on the Supreme Court, he remained a strong believer in individual rights and never wavered in his devotion to end discrimination. He was a key part of the Court's progressive majority that voted to uphold a woman's right to abortion (a woman's right to end a pregnancy). His majority opinions (statements issued by a judge) covered such areas as the environment, the right of appeal of persons convicted of drug charges, failure to report for and submit to service in the U.S. armed forces, and the rights of Native Americans.

Later years

The years when Ronald Reagan (1911–) and George Bush (1924–) occupied the White House were a time of sadness for Marshall, as the influence of liberals (those open to and interested in change) on the Supreme Court declined. In 1987 Marshall negatively criticized President Reagan in an interview with Ebony as "the bottom" in terms of his commitment to African Americans. He later told the magazine, "I wouldn't do the job of dogcatcher for Ronald Reagan." Marshall viewed the actions of the conservative (those interested in maintaining traditions) Republican presidents as a step back to the days when "we (African Americans) didn't really have a chance." Marshall was greatly disappointed when his friend and liberal colleague (coworker), Justice William J. Brennan Jr. (1906–1997), retired from the Supreme Court because of to ill health. Marshall vowed to serve until he was 110; however, he was finally forced by illness to give up his seat in 1991. He died in 1993 at the age of eighty-four.

Justice Marshall had been born during the administration of Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) but had lived to see African Americans rise to positions of power and influence in America. To a great degree, the progress of African Americans toward equal opportunity was aided by the legal victories won by him. By his death, he was considered a hero. His numerous honors included more than twenty honorary degrees from educational institutions in America and abroad. The University of Maryland Law School was named in his honor, as were a variety of elementary and secondary schools around the nation. During his life he received the NAACP's Spingarn Medal (1946), the Negro Newspaper Publisher Association's Russwurm Medal (1948), and the Living Makers of Negro History Award of the lota Phi Lambda Sorority (1950). His name was inscribed on the honor roll of the Schomburg History Collection of New York for the advancement of race relations. He enjoyed family life with his second wife and their two sons, who themselves pursued careers in public life. Dignified and solemn in manner, but blessed with a sense of humor, Marshall's career was an example of the power and possibility of American democracy.

For More Information

Arthur, Joe. The Story of Thurgood Marshall: Justice for All. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Books for Young Readers, 1995.

Hitzeroth, Deborah, and Sharon Leon. Thurgood Marshall. San Diego: Lucent Books, 1997.

Tushnet, Mark V. Making Civil Rights Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court 1936–1961. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Tushnet, Mark V. Making Constitutional Law: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court 1961–1991. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Williams, Juan. Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary. New York: Times Books, 1998.