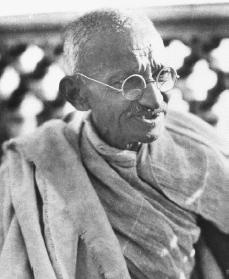

Mohandas Gandhi Biography

Born: October 2, 1869

Porbandar, India

Died: January 30, 1948

Delhi, India

Indian religious leader, reformer, and lawyer

Mohandas Gandhi was an Indian revolutionary and religious leader who used his religious power for political and social reform. Although he held no governmental office, he was the main force behind the second-largest nation in the world's struggle for independence.

Early years

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, India, a seacoast town in the Kathiawar Peninsula north of Bombay, India. His wealthy family was from one of the higher castes (Indian social classes). He was the fourth child of Karamchand Gandhi, prime minister to the raja (ruler) of three small city-states, and Purtlibai, his fourth wife. Gandhi described his mother as a deeply religious woman who attended temple (a place for religious worship) service daily. Mohandas was a small, quiet boy who disliked sports and was only an average student. At the age of thirteen he did not even know in advance that he was to marry Kasturbai, a girl his own age. The childhood ambition of Mohandas was to study medicine, but as this was considered beneath his caste, his father persuaded him to study law instead. After his marriage Mohandas finished high school and tutored his wife.

In September 1888 Gandhi went to England to study. Before leaving India, he promised his mother he would try not to eat meat. He was an even stricter vegetarian while away than he had been at home. In England he studied law but never completely adjusted to the English way of life. He became a lawyer in 1891 and sailed for Bombay. He attempted unsuccessfully to practice law in Rajkot and Bombay, then for a brief period served as lawyer for the prince of Porbandar.

South Africa: the beginning

In 1893 Gandhi accepted an offer from a firm of Muslims to represent them legally in Pretoria, the capital of Transvaal in the Union of South Africa. While traveling in a first-class train compartment in Natal, South Africa, a white man asked Gandhi to leave. He got off the train and spent the night in a train station meditating. He decided then to work to end racial prejudice. He had planned to stay in South Africa for only one year, but this new cause kept him in the country until 1914. Shortly after the train incident he called his first meeting of Indians in Pretoria and attacked racial discrimination (treating a certain group of people differently) by whites. This launched his campaign for improved legal status for Indians in South Africa, who at that time suffered the same discrimination as black people.

In 1896 Gandhi returned to India to take his wife and sons to Africa and to inform his countrymen of the poor treatment of Indians there. News of his speeches filtered back to Africa, and when Gandhi returned, an angry mob threw stones and attempted to lynch (to murder by mob action and without lawful trial) him.

Spiritual development

Gandhi began to do day-to-day chores for unpaid boarders of the lowest castes and encouraged his wife to do the same. He decided to buy a farm in Natal and return to a simpler way of life. He began to fast (not eat). In 1906 he became celibate (not engaging in sexual intercourse) after having fathered four sons, and he preached Brahmacharya (vow of celibacy) as a means of birth control and spiritual purity. He also began to live a life of voluntary poverty.

During this period Gandhi developed the concept of Satyagraha, or soul force. He wrote: "Satyagraha is not predominantly civil disobedience, but a quiet and irresistible pursuit of truth." Truth was throughout his life Gandhi's chief concern, as reflected in the subtitle of his Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Gandhi also developed a basic concern for the means used to achieve a goal.

In 1907 Gandhi urged all Indians in South Africa to defy a law requiring registration and fingerprinting of all Indians. For this activity he was imprisoned for two months but released when he agreed to voluntary registration. During Gandhi's second stay in jail he read the American essayist Henry David Thoreau's (1817–1862) essay "Civil Disobedience," which left a deep impression on him. He was also influenced by his correspondence with Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy

Reproduced by permission of

Gandhi decided to create a place for civil resisters to live in a group environment. He called it the Tolstoy Farm. By this time he had abandoned Western dress for traditional Indian garb. Two of his final legal achievements in Africa were a law declaring Indian (rather than only Christian) marriages valid, and the end of a tax on former indentured (bound to work and unable to leave for a specific period of time) Indian labor. Gandhi regarded his work in South Africa as completed.

By the time Gandhi returned to India in January 1915, he had become known as "Mahatmaji," a title given him by the poet Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). This title means "great soul." Gandhi knew how to reach the masses and insisted on their resistance and spiritual growth. He spoke of a new, free Indian individual, telling Indians that India's cages were self-made.

Disobedience and return to old values

The repressive Rowlatt Acts of 1919 (a set of laws that allowed the government to try people accused of political crimes without a jury) caused Gandhi to call a general hartal, or strike (when workers refuse to work in order to obtain rights from their employers), throughout the country. But he called it off when violence occurred against Englishmen. Following the Amritsar Massacre of some four hundred Indians, Gandhi responded by not cooperating with British courts, stores, and schools. The government agreed to make reforms.

Gandhi began urging Indians to make their own clothing rather than buy British goods. This would create employment for millions of Indian peasants during the many idle months of the year. He cherished the ideal of economic independence for each village. He identified industrialization (increased use of machines) with materialism (desire for wealth) and felt that it stunted man's growth. Gandhi believed that the individual should be placed ahead of economic productivity.

In 1921 the Congress Party, a group of various nationalist (love of one's own nation and cultural identity) groups, again voted for a nonviolent disobedience campaign. Gandhi had come to realize that India's reliance on Britain had made India more helpless than ever. In 1922 Gandhi was tried and sentenced to six years in prison, but he was released two years later for an emergency appendectomy (surgery to remove an inflamed appendix). This was the last time the British government tried Gandhi.

Fasting and the protest march

One technique Gandhi used frequently was the fast. He firmly believed that Hindu-Muslim unity was natural and he undertook a twenty-one-day fast to bring the two communities together. He also fasted during a strike of mill workers in Ahmedabad. Another technique he developed was the protest march. In response to a British tax on all salt used by Indians, a severe hardship on the peasants, Gandhi began his famous twenty-four-day "salt march" to the sea. Several thousand marchers walked 241 miles to the coast in protest of the unfair law.

Another cause Gandhi supported was improving the status of members of the lower castes, or Harijans. On September 20, 1932, Gandhi began a fast for the Harijans, opposing a British plan for a separate voting body for them. As a result of Gandhi's fast, some temples were opened to exterior castes for the first time in history.

Gandhi devoted the years 1934 through 1939 to the promotion of making fabric, basic education, and making Hindi the national language. During these years he worked closely with Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964) in the Congress Working Committee. Despite differences of opinion, Gandhi designated Nehru his successor, saying, "I know this, that when I am gone he will speak my language."

World War II and beyond

England's entry into World War II (1939–45; when the United States, France, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union fought against Germany, Italy, and Japan) brought India in without its consent. Because Britain had made no political compromises satisfactory to nationalist leaders, in August 1942 Gandhi proposed not to help in the war effort. Gandhi, Nehru, and other Congress Party leaders were imprisoned, touching off violence throughout India. When the British attempted to place the blame on Gandhi, he fasted for three weeks in jail. He contracted malaria (a potentially fatal disease spread by mosquitoes) in prison and was released on May 6, 1944.

When Gandhi emerged from prison, he sought to stop the creation of a separate Muslim state of Pakistan, which Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876–1948) was demanding. Jinnah declared August 16, 1946, a "Direct Action Day." On that day, and for several days following, communal killings left five thousand dead and fifteen thousand wounded in Calcutta alone. Violence spread through the country.

Extremely upset, Gandhi went to Bengal, saying, "I am not going to leave Bengal until the last embers of trouble are stamped out." But while he was in Calcutta forty-five hundred more people were killed in Bihar. Gandhi, now seventy-seven, warned that he would fast to death unless Biharis reformed. Either Hindus and Muslims would learn to live together or he would die in the attempt. The situation there calmed, but rioting continued elsewhere.

Drive for independence

In March 1947 the last viceroy, Lord Mountbatten (1900–1979), arrived in India with instructions to take Britain out of India by June 1948. The Congress Party by this time had agreed to separation, since the only alternative appeared to be continuation of British rule. Gandhi, despairing because his nation was not responding to his plea for peace and brotherhood, refused to participate in the independence celebrations on August 15, 1947. On September 1, 1947, after an angry Hindu mob broke into the home where he was staying in Calcutta, Gandhi began to fast, "to end only if and when sanity returns to Calcutta." Both Hindu and Muslim leaders promised that there would be no more killings, and Gandhi ended his fast.

On January 13, 1948, Gandhi began his last fast in Delhi, praying for Indian unity. On January 30, as he was attending prayers, he was shot and killed by Nathuram Godse, a thirty-five-year-old editor of a Hindu Mahasabha extremist newspaper in Poona.

For More Information

Barraclough, John. Mohandas Gandhi. Des Plaines, IL: Heinemann Interactive Library, 1998.

Clement, Catherine. Gandhi: The Power of Pacifism. New York: H. N. Abrams, 1996.

Gandhi, Mohandas. Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. 2 vols. 2d ed. Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1954.

Gandhi, Mohandas. The Essential Gandhi, an Anthology. Edited by Louis Fischer. New York: Random House, 1962. Reprint, New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Martin, Christopher. Mohandas Gandhi. Minneapolis: Lerner, 2001.

-----

Though this appears to be a small detail ... it was a major turn of events his life.

Thank you for the information.