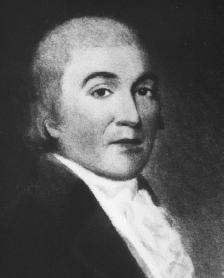

Noah Webster Biography

Born: October 16, 1758

West Hartford, Connecticut

Died: May 23, 1843

New Haven, Connecticut

American lexicographer

Noah Webster, American lexicographer (one who compiles a dictionary), remembered now almost solely as the compiler of a continuously successful dictionary, was for half a century among the more influential and most active literary men in the United States.

Early life

Noah Webster was born on October 16, 1758, in West Hartford, Connecticut. The fourth son of five children of Noah and Mercy Steele Webster, young Noah showed exceptional scholarly talents as a child, and his father sacrificed much in order that his son would gain the best education available.

In 1774, at age sixteen, Webster entered Yale College, sharing literary ambitions with his classmate Joel Barlow and tutor Timothy Dwight. His college years were interrupted by terms of military service. After his graduation in 1778, Noah began studying law, but because his father could no longer support him, he took a job as a schoolmaster in Hartford, Litchfield, and Sharon, all in Connecticut. Meanwhile, he read widely and studied law. He was admitted to the bar (an association for lawyers) and received his master of arts degree in 1781. Dissatisfied with the British-made textbooks available for teaching, he determined to produce his own. He had, he said, "too much pride to stand indebted to Great Britain for books to learn our children."

Schoolmaster to America

Webster soon developed the first of his long series of American schoolbooks, a speller titled A Grammatical Institute of the English

Courtesy of the

Webster toured the United States from Maine to Georgia selling his textbooks, convinced that "America must be as independent in literature as she is in politics, as famous for arts as for arms, " but that to accomplish this she must protect by copyright (the legal right of artistic work) the literary products of her countrymen. He pleaded so effectively that uniform copyright laws were passed early in most of the states, and it was largely through his continuing effort that Congress in 1831 passed a bill which ensured protection to writers. On his travels he also peddled (sold from door to door) his Sketches of American Policy (1785), a vigorous plea on behalf of the Federalists, a then-popular political party that believed in a strong central government. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he paused briefly to teach school and see new editions of his Institute through the press, he published his politically effective An Examination into the Leading Principles of the Federal Constitution (1787).

In New York City, Webster established the American Magazine (1787–88), which he hoped might become a national periodical (magazine distributed regularly). In it he pled for American intellectual independence, education for women, and the support of Federalist ideas. Though it survived for only twelve monthly issues, it is remembered as one of the most lively, bravely adventuresome of early American periodicals. He continued as a political journalist with such pamphlets as The Effects of Slavery on Morals and Industry (1793), The Revolution in France (1794), and The Rights of Neutral Nations (1802).

Language reform

But Webster's principal interest became language reform, or improvement. As he set forth his ideas in Dissertations on the English Language (1789), theatre should be spelled theater; machine, masheen; plough, plow; draught, draft. For a time he put forward claims for such reform in his readers and spellers and in his Collection of Essays and Fugitiv [sic] Writings (1790), which encouraged "reezoning," "yung" persons, "reeding," and a "zeel" for "lerning"; but he was too careful a Yankee to allow odd behavior to stand in the way of profit. In The Prompter (1790) he quietly lectured his countrymen in corrective essays written plainly, in a simple and to-the-point style.

After Webster married in 1789, he practiced law in Hartford for four years before returning to New York City to edit the city's first daily newspaper, the American Minerva (1793–98). Tiring of the controversy (open to dispute) brought on by his forthright expression of Federalist opinion, he retired to New Haven, Connecticut, to write A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases (1899) and to put together a volume of Miscellaneous Papers (1802).

The dictionaries

From this time on, Webster gave most of his attention to preparing more schoolbooks, including A Philosophical and Practical Grammar of the English Language (1807). But he was primarily concerned with assembling A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806); its shorter version, A Dictionary … Compiled for the Use of Common Schools (1807, revised 1817); and finally, in two volumes, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828). In range this last surpassed (went beyond) any dictionary of its time. A second edition, "corrected and enlarged" (1841), became known popularly as Webster's Unabridged. Conservative contemporaries (people of the same time or period), alarmed at its unorthodoxies (untraditional) in spelling, usage, and pronunciation and its proud inclusion of Americanisms, dubbed the work as "Noah's Ark." However, after Webster's death the rights were sold in 1847 to George and Charles Merriam, printers in Worcester, Massachusetts; and the dictionary has become, through many revisions, the foundation and defender of effective American lexicography.

Webster's other late writings included A History of the United States (1832), a version of the Bible (1832) cleansed of all words and phrases dangerous to children or "offensive especially to females," and a final Collection of Papers on Political, Literary and Moral Subjects (1843). Tall, redheaded, lanky, humorless, he was the butt of many cruel criticisms in his time. Noah Webster died in New Haven on May 23, 1843.

For More Information

Micklethwait, David. Noah Webster and the American Dictionary. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000.

Moss, Richard J. Noah Webster. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1984.

Rollins, Richard M. The Long Journey of Noah Webster. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980.

Snyder, K. Alan. Defining Noah Webster. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1990.

Unger, Harlow G. Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: