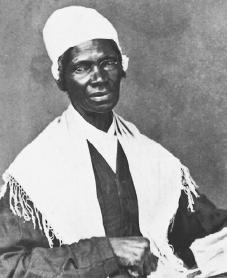

Sojourner Truth Biography

Born: 1797

Ulster County, New York

Died: November 26, 1883

Battle Creek, Michigan

African American abolitionist

One of the most famous nineteenth-century black American women, Sojourner Truth was an uneducated former slave who actively opposed slavery. Though she never learned to read or write, she became a moving speaker for black freedom and women's rights. While many of her fellow black abolitionists (people who campaigned for the end of slavery) spoke only to blacks, Truth spoke mainly to whites. While they spoke of violent uprisings, she spoke of reason and religious understanding.

Sojourner Truth was born Isabella Baumfree around 1797 on an estate owned by Dutch settlers in Ulster County, New York. She was the second youngest in a slave family of the ten or twelve children of James Baumfree and his wife Elizabeth (known as "Mau-Mau Bett"). When her owner died in 1806, Isabella was put up for auction. Over the next few years, she had several owners who treated her poorly. John Dumont purchased her when she was thirteen, and she worked for him for the next seventeen years.

In 1817 the state of New York passed a law granting freedom to slaves born before July 4, 1799. However, this law declared that those slaves could not be freed until July 4, 1827. While waiting ten years for her freedom, Isabella married a fellow slave named Thomas, with whom she had five children. As the date of her release approached, she realized that Dumont was plotting to keep her enslaved. In 1826 she ran away, leaving her husband and her children behind.

Wins court case to regain son

Three important events took place in Isabella's life over the next two years. She found refuge with Maria and Isaac Van Wagenen, who bought her from Dumont and gave her freedom. She then underwent a religious experience, claiming from that point on she could talk directly to God. Lastly, she sued to retrieve her son Peter, who had been sold illegally to a plantation owner in Alabama. In 1828, with the help of a lawyer, Isabella became the first black woman to take a white man to court and win.

Reproduced by permission of

Soon thereafter, Isabella moved with Peter to New York City and began following Elijah Pierson, who claimed to be a prophet. He was soon joined by another religious figure known as Matthias, who claimed to be the Messiah. They formed a cult known as the "Kingdom" and moved to Sing Sing (renamed Ossining) in southeast New York in 1833. Isabella grew apart from them and stayed away from their activities. But when Matthias was arrested for murdering Pierson, she was accused of being an accomplice. A white couple in the cult, the Folgers, also claimed that Isabella had tried to poison them. For the second time, she went to court. She was found innocent in the Matthias case, and decided to file a slander suit against the Folgers. In 1835 she won, becoming the first black person to win such a suit against a white person.

Changes name

For the next eight years, Isabella worked as a household servant in New York City. In 1843, deciding her mission was to preach the word of God, Isabella changed her name to Sojourner Truth and left the city. Truth traveled throughout New England, attending and holding prayer sessions. She supported herself with odd jobs and often slept outside. At the end of the year, she joined the Northampton Association, a Massachusetts community founded on the ideas of freedom and equality. It is through the Northampton group that Truth met other social reformers and abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass (1817–1895), who introduced her to their movement.

During the 1850s, the issue of slavery heated up in the United States. In 1850 Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, which allowed runaway slaves to be arrested and jailed without a jury trial. In 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Dred Scott (1795?–1858) that slaves had no rights as citizens and that the government could not outlaw slavery in new territories.

Lectures to hostile crowds

The results of the Scott case and the unsettling times did not frighten Truth away from her mission. Her life story, Narrative of Sojourner Truth, cowritten with Olive Gilbert, was published in 1850. She then headed west and made stops in town after town to speak about her experiences as a slave and her eventual freedom. Her colorful and down-to-earth style often soothed the hostile crowds she faced. While on her travels, Truth noted that while women could be leaders in the abolitionist movement, they could neither vote nor hold public office. Realizing she was discriminated against on two fronts, Truth became an outspoken supporter of women's rights.

By the mid-1850s, Truth had earned enough money from sales of her popular autobiography to buy land and a house in Battle Creek, Michigan. She continued her lectures, traveling throughout the Midwest. When the Civil War began in 1861, she visited black troops stationed near Detroit, Michigan, offering them encouragement. Shortly after meeting U.S. president Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) in October 1864, she decided to stay in the Washington area to work at a hospital and counsel freed slaves.

Continues fight for freed slaves

Following the end of the Civil War, Truth continued to work with freed slaves. After her arm had been dislocated by a streetcar conductor who had refused to let her ride, she fought for and won the right for blacks to share Washington streetcars with whites. For several years she led a campaign to have land in the West set aside for freed blacks, many of whom were poor and homeless after the war. She carried on her lectures for the rights of blacks and women throughout the 1870s. Failing health, however, soon forced Truth to return to her Battle Creek home. She died there on November 26, 1883.

For More Information

Gilbert, Olive. Narrative of Sojourner Truth. Boston: Self-published, 1850. Reprint, New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

Krass, Peter. Sojourner Truth. New York: Chelsea House, 1988.

Mabee, Carleton, with Susan Mabee Newhouse. Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend. New York: New York University Press, 1993.

McKissack, Patricia, and Fredrick McKissack. Sojourner Truth: A Voice for Freedom. Hillside, NJ: Enslow, 1992.

Painter, Nell Irvin. Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. New York: Norton, 1996.

Rockwell, Anne F. Only Passing Through: The Story of Sojourner Truth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.