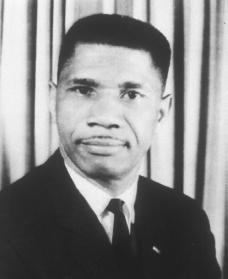

Medgar Evers Biography

Born: July 19, 1925

Decatur, Mississippi

Died: June 12, 1963

Jackson, Mississippi

African American civil and human rights activist

Medgar Evers, field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was one of the most important figures of the African American civil rights movement. He paid for his beliefs with his life, becoming the first major civil rights leader to be assassinated in the 1960s. His death prompted President John F. Kennedy (1917–63) to ask Congress for a national civil rights bill, which President Lyndon Johnson (1908–73) signed into law in 1964.

A course in racism

Medgar Evers was born on July 19, 1925 in Decatur, Mississippi, the third of four children of a small farm owner. In The Martyrs: Sixteen Who Gave Their Lives for Racial Justice, Jack Mendelsohn quoted Evers on his childhood. "I was born in Decatur here in Mississippi, and when we were walking to school in the first grade white kids in their schoolbuses would throw things at us and yell filthy things," the civil rights leader recollected. "This was a mild start. If you're a kid in Mississippi this is the elementary course."

By the time Evers reached adulthood he had, as he put it in Mendelsohn's book, moved on from this "elementary course" in racism (a dislike or disrespect of someone based on the color of their skin) and "graduated pretty quickly." In the Mississippi of Evers's boyhood, African Americans were routinely terrorized by the violence of racist whites. Lynching (the killing of a person by a group of people outside of the law) was common, and discrimination (treating people differently based on their race) was an everyday fact. However, Evers was fortunate to have an example of strong independence and pride in his own father. James Evers, Medgar's father, refused to get off the sidewalk to let a white man pass as was customary. Unlike many African Americans in the South, he also owned his own land.

The young Medgar Evers was determined not to cave in to hardship. He walked twelve miles each way to earn his high school diploma and then joined the U.S. Army during World War II (1939–45), a war that involved countries in many parts of the world. He was discharged from the army in 1946.

Joining the NAACP

After the war Evers returned to Decatur, where he was reunited with his brother Charlie. The young men decided they wanted to vote in the next election. Since the aim of discrimination was to keep power in the hands of the South's white population, preventing and discouraging African Americans from voting was a major tactic of white racists. When election day came, the Evers brothers found their polling place blocked by an armed crowd of whites, estimated by Evers to be two hundred strong.

Evers and his brother did not vote that day. Instead they joined the NAACP and became active in its ranks. Evers was already busy with NAACP projects when he was a student at Alcorn A&M College in Lorman, Mississippi. He entered college in 1948, majored in business administration, and graduated in 1952. During his senior year he married Myrlie Beasley. After graduation the young couple lived on his earnings as an insurance salesman.

Reproduced by permission of

Evers continued to witness the victims of hate and racism. He saw the terrible living conditions of the rural blacks he visited while working for his company. Then in 1954 he witnessed an attempted lynching during a time of great personal sorrow. His father was dying in the hospital, and while visiting him Evers went to get a breath of air outside. As he later related in The Martyrs, "On that very night a Negro had fought with a white man in Union [Mississippi] and a white mob had shot the Negro in the leg. The police brought the Negro to the hospital but the mob was outside … armed with pistols and rifles, yelling for the Negro. I walked out into the middle of it.… It seemed that this would never change."

Campaigning for civil rights

Evers soon went to work for the NAACP full time. Within two years he was named to the important position of state field secretary for the organization. Still in his early thirties, he was one of the most well-known NAACP members in his state. With his wife and children, he moved to Jackson, Mississippi, where he worked closely with black church leaders and other civil rights activists. Evers spoke constantly of the need to overcome hatred and promote understanding and equality between the races. It was not a message that everyone in Mississippi wanted to hear.

Evers was featured on a nine-man death list in the deep South as early as 1955. He and his family endured many threats and other violent acts, making them well aware of the danger surrounding Evers because of his activities. Still he persisted in his efforts to end segregation (separating people based solely on their race) in public facilities, schools, and restaurants. He organized voter-registration drives and demonstrations. His days were filled with meetings, economic boycotts (to make a stand against a person or a business by refusing to buy their goods, products, or businesses), marches, prayer services, picket lines, and bailing other demonstrators out of jail.

A fallen leader

On June 12, 1963, President Kennedy made an address to the nation. Kennedy believed that whites standing in the way of civil rights for blacks represented "a moral crisis" and pledged his support to federal action on integration, or ending segregation. That same night, Evers returned home just after midnight from a series of NAACP functions. As he left his car, he was shot in the back. Evers died shortly thereafter at the hospital.

When the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) looked into Evers's murder, a suspect was uncovered, Byron de la Beckwith (1920–2001), who was an outspoken opponent of integration and a member of a group called the Mississippi's White Citizens Council. A gun found 150 feet from the site of the shooting had Beckwith's fingerprint on it. Several witnesses placed Beckwith in Evers's neighborhood that night. However, he denied shooting Evers and claimed his gun had been stolen days before the incident. Beckwith, too, produced witnesses who swore that he was some sixty miles from Evers's home on the night of the murder.

Beckwith was tried twice in Mississippi for Evers's murder during the 1960s, once in 1964 and again the following year. Both trials ended in hung juries. After the second trial, Myrlie Evers took her children and moved to California. However, her strong belief that justice was never served in her husband's case kept Mrs. Evers involved in the search for new evidence. In 1991, Byron de la Beckwith was arrested a third time on charges of murdering Medgar Evers. He was finally convicted of the crime in 1994.

The Evers legacy

In some ways, the death of Medgar Evers was a milestone in the hard-fought civil rights war that rocked America in the 1950s and 1960s. While Evers's assassination foreshadowed the violence to come, it also inspired civil rights leaders and their followers to work for their cause with still more dedication. Above all, it inspired them to work with the courage that Evers himself had shown.

For More Information

Altman, Susan. Extraordinary Black Americans from Colonial to Contemporary Times. Chicago: Children's Press, 1989.

Brown, Jennie. Medgar Evers. Los Angeles: Melrose Square, 1994.

DeLaughter, Bobby. Never Too Late: A Prosecutor's Story of Justice in the Medgar Evers Case. New York: Scribner, 2001.

Nossiter, Adam. Of Long Memory: Mississippi and the Murder of Medgar Evers. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1994.

Ribeiro, Myra. The Assassination of Medgar Evers. New York: Rosen, 2002.