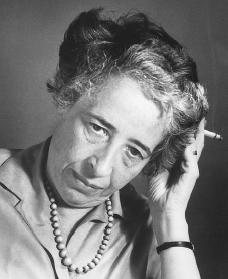

Hannah Arendt Biography

Born: October 14, 1906

Hanover, Germany

Died: December 4, 1975

New York, New York

German philosopher and writer

A Jewish girl forced to flee Germany during World War II (1939–45), Hannah Arendt analyzed major issues of the twentieth century and produced an original and radical political philosophy.

Early life and career

Hannah Arendt was born on October 14, 1906, in Hanover, Germany, the only child of middle-class Jewish parents of Russian descent. A bright child whose father died in 1913, she was encouraged by her mother in intellectual and academic pursuits. As a university student in Germany she studied with the most original scholars of that time: Rudolf Bultmann (1888–1976) and Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) in philosophy; the phenomenologist (one who studies human awareness) Edmund Husserl (1859– 1938); and the existentialist (one who studies human existence) Karl Jaspers (1883– 1969). In 1929 Arendt received her doctorate degree and married Gunther Stern.

In 1933 Arendt was arrested and briefly imprisoned for gathering evidence of Nazi anti-Semitism (evidence that proved the Nazis were a ruthless German army regime aimed at ridding Europe of its Jewish population). Shortly after the outbreak of World War II she fled to France, where she worked for Jewish refugee organizations (organizations aimed at helping Jews that were forced to flee Germany). In 1940 she and her second husband, Heinrich Blücher, were held captive in southern France. They escaped and made their way to New York in 1941.

Reproduced by permission of the

Throughout the war years Arendt wrote a political column for the Jewish weekly Aufbau, and began publishing articles in leading Jewish journals. As her circle of friends expanded to include leading American intellectuals, her writings found a wider audience. Her first major book, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), argued that modern totalitarianism (government with total political power without competition) was a new and distinct form of government that used terror to control the mass society. "Origins" was the first major effort to analyze the historical conditions that had given rise to Germany's Adolph Hitler (1889–1945) and Russia's Joseph Stalin (1879–1953), and was widely studied in the 1950s.

Labor, work, and action

A second major work, The Human Condition (1958), followed. Here, and in a volume of essays, Between Past and Future (1961), Arendt clearly defined themes from her earlier work: in a rapidly developing world, humans were no longer able to find solutions in established traditions of political authority, philosophy, religion, or even common sense. Her solution was as radical (extreme) as the problem: "to think what we are doing."

The Human Condition established Arendt's academic reputation and led to a visiting appointment at Princeton University—the first time a woman was a full-time professor there. On Revolution (1963), a volume of her Princeton lectures, expressed her enthusiasm at becoming an American citizen by exploring the historical background and requirements of political freedom.

In 1961 Arendt attended the trial in Jerusalem of Adolf Eichmann (1906–1962), a Nazi who had been involved in the murder of large numbers of Jews during the Holocaust (when Nazis imprisoned or killed millions of Jews during World War II). Her reports appeared first in The New Yorker and then as Eichmann in Jerusalem (1964). They were frequently misunderstood and rejected, especially her claim that Eichmann was more of a puppet than radically evil. Her public reputation among even some former friends never recovered from this controversy.

Later career

At the University of Chicago (1963–1967) and the New School for Social Research in New York City (1967–1975), Arendt's brilliant lectures inspired countless students in social thought, philosophy, religious studies, and history. Frequently uneasy in public, she was an energetic conversationalist in smaller gatherings. Even among friends, though, she would sometimes excuse herself and become totally absorbed in some new line of thought that had occurred to her.

During the late 1960s Arendt devoted herself to a variety of projects: essays on current political issues, such as civil unrest and war, published as Crises of the Republic (1972); portraits of men and women who offered some explanation on the dark times of the twentieth century, which became Men in Dark Times (1968); and a two-volume English edition of Karl Jaspers's The Great Philosophers (1962 and 1966).

In 1973 and 1974 Arendt delivered the well-received Gifford Lectures in Scotland, which were later published as The Life of the Mind (1979). Tragically, Arendt never completed these lectures as she died of a heart attack in New York City on December 4, 1975.

Arendt was honored throughout her later life by a series of academic prizes. Frequently attacked for controversial and sometimes odd judgments, Hannah Arendt died as she lived—an original interpreter of human nature in the face of modern political disasters.

For More Information

Kristeva, Julia. Hannah Arendt. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

McGowan, John. Hannah Arendt: An Introduction. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: